NEXT TO ME for MARIE CLAIRE ITALIA

A building like many others, in the heart of Porta Palazzo, the Turin casbah with its 55 ethnicities.

The cradle of the biggest multiethnic market in Europe. On the stairs the silence is broken by the buzz behind the doors. From each apartment you can heard voices of different languages, that remain contained inside: here nobody knows each other.

This is the place that welcomed me for four years, a building where everything seemed to me immediately so different to become familiar. A house. Where, however, nobody knows anything about the other's lives.

The first one opening me the door, flat n° 9, is Bakary Sane, 58 years, senegalese from Dakar. Mechanic.

Bakary is been living in Italy for 19 years, 15 here in Porta Palazzo. "All of them spent working", he tells me while he invites me to share the lunch with him, in the same hot bowl. We eat together a typical Senegalese dish made with rice and meat.

Son of a police man and born in a police station in Dakar. Bakary graduated in mechanics and he worked for two years in Senegal. He arrived for the first time in Italy visiting a Senegalese friend. She realized immediately that his work in Italy would have been paid more than in his country. After a short period in Paris, he arrived in Turin. Even he's happy here, he misses his family. He sends money to Senegal every month, even if he's risking to lose his own house to pay the building's restructuring costs.

A sunny man, able to make your day just smiling on the stairs. He's fully integrated in our culture, but he tells me about the discriminations suffered, especially at work. Racial discrimination was commonplace. A lot of people let you know that they are bothered by the difference of the color of the skin, even if they don't tell that to your face. How do you call it? Hypocrisy, right? Anyway, I’ve never let people walked on me”

“Racism exists, all right. But it’s not natural. We humans have created it. And honestly I don’t understand it, because it bring us back and gets us away from the idea that we are all the same as human beings, sons of people that have always mixed together."

On the ground, his luggage. He's leaving for Senegal. He banked his vacations to have more time to stay with his family. He's happy but a bit melancholic. That month is never enough.

"If this country wants to go on, it cannot think itself as a country that doesn’t welcome other cultures. Who doesn’t understand it, doesn’t understand the world.”

With these words he says me goodbye, with those confident eyes, in which I can glimpse the secrets of his happiness: show others that the problem doesn’t exist.

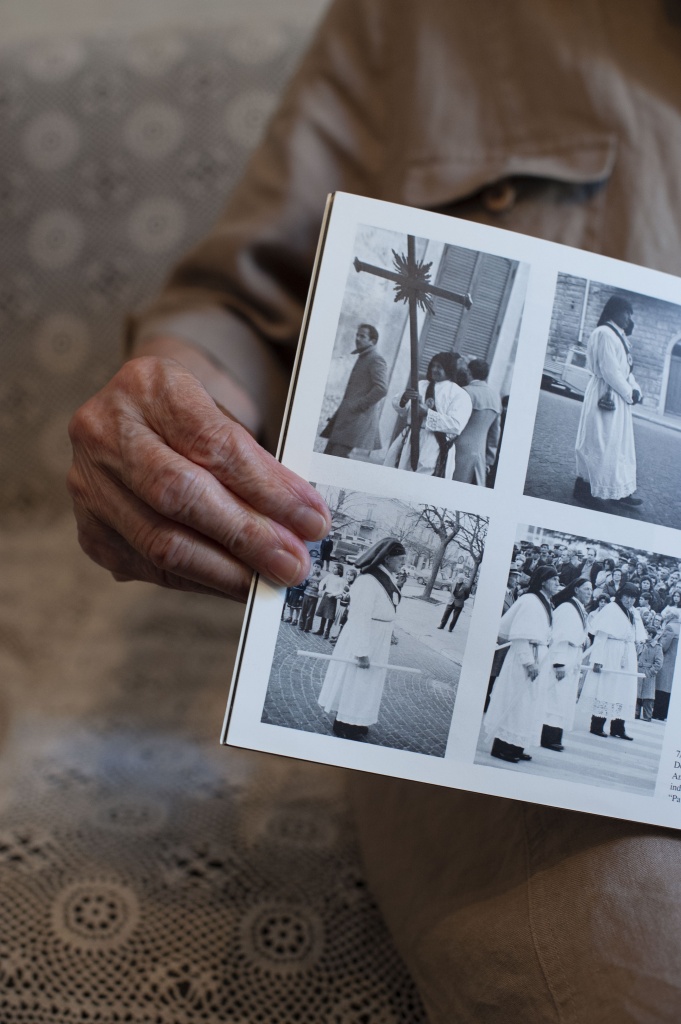

One floor below, flat n° 7, I ring the bell for who has pushed me to tell this building. Filomena Caputi, born in Ruvo di Puglia, province of Bari, 87 years ago.

Settled in Turin to follow his husband, Fiat worker, Filomena arrived in Porta Palazzo in 1962. 56 years. She has been walked out that door for 56 years. Lifelong housewife, she really lived the building, having had to look after her sick mother-in-law for 12 years. An old-timer woman, but that’s why she is free from any prejudice. Because Filomena lived herself the immigration. “I’ve never felt my self discriminated against as a southern. I think it depends by your attitude. I’ve always been an open mind woman. I’ve never wanted be limited to my culture and my traditions, like a lot of southerners did.

When she arrived in Turin from Ruvo di Puglia, province of Bari, Filomena was the unwanted one. “We got the house just because the owner knew a relative of mine who have lived here since the Fifties. People didn’t trust southerners. They considered us dirty, thieves and wild.” The condo stairs, the district streets, the marker square. Filomena's places. Those places the made Porta Palazzo a real community. “It was like living in a small village, around the corner of the centre of Turin. In the streets down here there was everything: from the milkman to the tailor."

"Porta Palazzo was the biggest market in Europe and had the power to animate the surrounding streets.It was a real community, made by different people and cultures. You could stop by everyone and everyday you always had something to learn” she tells me on a hot summer afternoon, while she makes some coffee.

Filomena has been an housewife and a tailor. She has always been at home. And from those windows she could see everything. “In the 80ies Porta Palazzo started to become a tough district with the Barriera di Milano. Murders, raped women, robberies, drug dealing. It was unlivable. There was also little control. It was a free zone." The foreign immigration of those years was perceived as a discomfort ". A disease that is still felt today, but seems to be sedated by sporadic controls and general indifference. "We used to dry clothes all together in the courtyard. We told each other our days, our problems. Even if we came from different parts of the world, we all felt the same ».

She does not have the distrust typical of his age. «Porta Palazzo pushes me to talk to people other than me. Now I chat more with foreigners than with Italians. We almost don't do it anymore. Before, there was not so much fear of the difference as today, because the sense of community was strong. People helped each other and shared everyday life. We met hanging out the laundry down in the yard; we talked, we told each other our days, our problems. Even if we came from different parts of the world, we all felt the same." Fearless with her shopping cart, Mrs. Filomena is known in the streets below. When she can, she always stops to chat and never shows the mistrust typical of her age. "I like Porta Palazzo. It drives me to talk to people different from me. Now I speak more with foreigners than with Italians." "The secret is to show, to expose yourself to others naturally, understanding that's the foundation not only of a small community, but of the whole society".

I go up one floor. Flat n°14. Here there's Rida Ladini, 21 years old, the youngest tenant of my project. Born not far from Agadir in Morocco, he's a mechanical designer.

For 13 years Rida lived in Morocco. First, in a small village near Agadir and then in Casablanca. When he was 5 his mum left for Italy and he moved to the centre of Morocco, where he lived with his grandmother. After 3 years his mum came back to get him and his brother to bring them back in Italy.

His first meeting with Italy is in Pompiano, a small town in the province of Brescia. "I spoke a bit of Italian and when other boys made fun of me, I pretended to not understand and I went on. I even have got a medal of the Lega political party won for a cycling race" he tells laughing.

Rida arrived in Porta Palazzo 6 years ago. "For me it's the most beautiful district of Turin. Here's everything. As a Moroccan I could not ask for anything better. I have my community here, and I'm right around the corner from the city center. This is my home. " Rida calls Porta Palazzo a home. And it's the same for many people of his community. Sometimes here you forget to be in Italy and this brings the district to appear like a small ghetto. Even If I loved living the multiculturalism, in a certain way I have always suffered this aspect. It made me think that there weren't interest in Italian culture. And this was enough for me to judge integration as fake.

"When you're an immigrant, districts like this protect you. Many people here still think in Dirham, because they don't have the slightest interest in integrating."

The ghetto dimension helps to recreate a community, brings people closer and makes them feel really a part of something, especially if they don't fell themselves integrated by Italian people. "

In our building Rida knows everyone, but he tells me he found hard to communicate with younger people. "I do not understand young people who have this distrust. We are probably too influenced by this difficult and confusing years. And people prefer to close themselves in their own reality" he tells me while he prepares mint tea for me.

"I have to say that here my community contribute to create crime. They do it because they come from a completely different reality. In Morocco, If you do it, they mistreat you." "I am sure that if there were quality projects in Porta Palazzo, people would also stop selling drugs. I'm not justifying them, they choose their life. But they envy mine, my work, my being integrated. They tell me << You do well, while I'm here doing nothing>>. And do you know how I answer? I speak to them in Italian."

When I ask him what he's missing of his country, he surprises me: "Actually nothing, and do you know why? Because for me Italy is very similar to Morocco, especially here. We do not realize how much Mediterranean people look alike. And that's why we do not recognize ourselves as similar. I would not bring anything here from Morocco. Instead, I'd take an Italian to see my country" he tells me as he wraps his head with the tagelmust and wears the kaftan over the white shirt he wears every day to go to work. Rida deeply loves Italy, his work, the city in which he lives, our culture. At the same time he doesn't deny anything of his traditions. It's in his proud eyes he shows me pouring the mint tea that I see the integration. I wonder what can he taking away to Italian culture with that act.

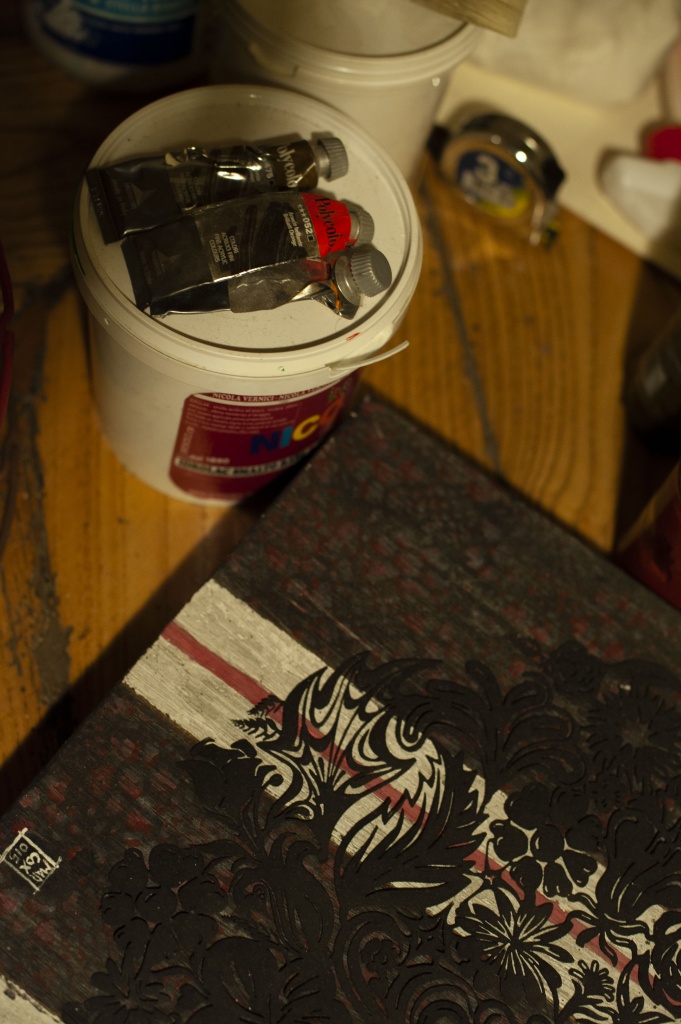

I go back to my floor, flat n°11, to interview my balcony neighbor, Marco Cossu, 51 years, painter.

Born in Moncalieri in 1967, Marcolived in the castle of the city for 3 years, since his father, a Sardinian sergeant of police, was instructor of biological and chemical weapons there. He has been a graphic designer, journalist, cameraman and artist. He was a true traveler, for work and for passion.

Marco grew up at Lingotto General Market, Turin's first major centre of diversity and trade. Anybody like him here knows multicultural districts. "Diversities for me are natural and necessary. My eyes don't see them." Porta Palazzo is a district in which some ethnic groups concentrate in a few blocks, leading you to think that is a conscious choice. Groups like the Moroccan one, that Marco knows well. "Porta Palazzo may be a choice at first, linked to the need to feel close to your own culture. They get the idea of Italy as a reality mythologized by relatives or friends who leave their country." "As just we once did around the world, they remain in the same neighborhood, because the sense of safety and protection is stronger than the desire for change that drives you to really integrate."

"Yes, the ghetto is there, but is not a living place, it's not physical. It is cultural. Your space is what they leave to you, it's given by those who, in a certain way, cut you off. And, naturally, it becomes your home, it protects you. It's enveloping. They want to feel comfortable, just like us. Those who ghettoize themselves do so because they feel ghettoized by others. " "It is not just mistrust, it is rejection, even unconscious. And who is a foreign can feel it, lives it in daily life and takes refuge where he obviously feels more comfortable.

"Forty years ago we did not judge immigrants in that way. Because we were better. There had been no September 11th. Many things had not been emphasized yet. It was the post-war period. We believed in our country as the Republic, we were not discouraged like toady. We really knew what equality was. This mentality is the result of what we experience, what we feel in the family, of what we learn from society. And if cultural tools are not developed in the opposite direction, ghettos will be more and more ghettos. "It's a mandatory and a cover integration", he tells me. Yes, because rejection is a common thought now. We oppose and refuse even before we know, without knowing anything about the others."

Society is going in one direction, the one that leads us to think individually, to consider other communities as antagonistic. "There must be the enemy. We are the ones who can not really see that in those who decide for us, but we see it in the difference. They teach us that they take away from us when it is what we have been doing for decades." Look how Africa was, he tells me by showing me the map of the African continent above his bed, dated 1956. "Every country speaks Portuguese, English, and French mainly. In any case, colonialism has no colors. He has interests. "Those interests that we do not want to see, because they remind us our our responsibilities, global and historical.

Like all the other condos, Marco sees in the rediscovery of communication the only antidote to today's mood. "Who really rules the world does not agree that there is a pure knowledge, the one that breaks down the preconceptions and that unites us all. Today, unfortunately, to communicate we must be mediated. "

Waiting for me, on the top floor, flat n°20, there's Giulia Perin, 30 years old, born in San Mauro Torinese.

Born in San Mauro Torinese, she moved to Turin at 24, but after only two years she moved again, this time for Indonesia, where she studied Texile Design, falling in love with the Asian handicraft.

At first, she was suspicious. We had really never talked to each other, although we were the only two girls who lived alone in that building. After having told her my project, she welcomed me into her home as a friend.

Giulia is a craftswoman, but six months a year she's a tour operator for Italian people in Indonesia.

"It's nice to show other people the world through your eyes, getting them free from all the thoughts we have about countries so different from us."

Giulia has traveled. And it shows. She has the experience and the clarity to understand who leaves his own country and with that his whole life, to look for a new one on the other side of the world. "Most of the people you see in Porta Palazzo come here to work. We travel to discover, for pleasure. If you don't see their interest for Italian culture, it's because they do not even have it for their countries."

"They are wary because of our haughtiness. We find difficult to build our lives. We're groping, but we are self-centered. We worry about us, and that's it. We are culturally poor and we are all too scared. Do you know what the truth is? We are embarrassed, because we don't know how to manage immigration, because of a country that has not been able to do so." Even with Giulia I understand that the lack of communication is primarily among us Italians, not just condominiums, but among the inhabitants of the neighborhood. "

The Neighborhood Space at the ground floor of our building is an example of our ignorance about community. An important and productive reality for Porta Palazzo, but that has never dialogued with the condos. "They should have to knock on all our doors, introduce themselves, invite us. It is the clear example of our ignorance about it. We create a reality like this but we don't know what community means" she tells me disappointed. We must understand again what it means to be democratic. If we help each other, it's good for everyone. And we must start from the building, at home, in the family. "

"Loving the difference." For four years I've read this quote written in all the languages on the Porta Palazzo covered market's facade. A cry of hope repeated so many times that I doubted it was true.

But something tells me that here, in this building, things could change. I can still picture my neighbors. Reaching out and knocking on the front door.

I understood that difference is really the next door friend.

AND YOU, DO YOU KNOW YOU NEXT-DOOR NEIGHBOUR?